Hydrotherapy: The Wonder Medicine Hidden in Plain Sight

Published

It’s just about the simplest cure imaginable, so basic we scarcely call it medicine: A bag of ice on a bruise. A hot bath after a long day. A cold washcloth on a feverish forehead. A warm water bottle on a sore neck.

Hydrotherapy, the therapeutic use of water, includes everyday remedies your mother probably taught you. It also includes a slew of powerful methods for easing muscle soreness, relieving cough and flu symptoms, reducing stress and other uses. In one form or another, they all use one of the most elemental materials on earth.

“Water is an amazingly complex yet simple substance that can do all kinds of healing things,” says Dean E. Neary, Jr., ND (‘96), chair of the Department of Physical Medicine at Bastyr University. “In this high-tech world, some of the best remedies are the most basic.”

Hydrotherapy is the first form of treatment students learn in Bastyr’s Doctor of Naturopathic Medicine program. For some, it’s one of the most appealing.

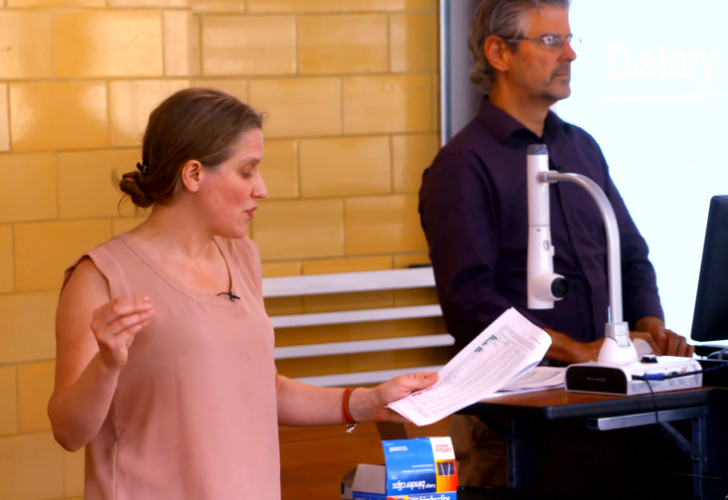

“I strongly believe in educating patients,” says Hannah Gordon, a fourth-year naturopathic medicine student. “I want to give my patients something they can do at home as a preventive way to support the fundamentals of health. If they get a sniffle, they know how to do a steam inhalation. They don’t need to visit a doctor for that.”

Now students have new facilities for practicing hydrotherapy on Bastyr’s Kenmore campus. A new hydrotherapy lab, part of extensive ground-floor renovations, will soon include bathing facilities, a sauna, massage tables, and hot-and-cold wraps from the physical medicine lab next door. The lab provides a home base for the Nature Cure Club, a student group that practices some of the most fundamental naturopathic therapies through open lab sessions and field trips.

Now students have new facilities for practicing hydrotherapy on Bastyr’s Kenmore campus. A new hydrotherapy lab, part of extensive ground-floor renovations, will soon include bathing facilities, a sauna, massage tables, and hot-and-cold wraps from the physical medicine lab next door. The lab provides a home base for the Nature Cure Club, a student group that practices some of the most fundamental naturopathic therapies through open lab sessions and field trips.

“We need hands-on experience,” says Gordon, the club’s president. “Practicing on each other now gives us confidence to work with our patients in the future. It develops our therapeutic touch.”

Receive, Give, Teach

Hydrotherapy begins with home remedies, but it also includes sophisticated methods for facilitating the body’s natural healing process. Those include peat baths, warm 20-minute soaks with pain-relieving minerals. They also include alternating hot and cold treatments to facilitate muscle recovery. One popular regimen is showers of three minutes hot water followed by 30 seconds cold water, repeated several times. Constitutional hydrotherapy, a distinct method, stimulates the body’s vital force and immune system through hot and cold towels and electrotherapy devices.

Hydrotherapy begins with home remedies, but it also includes sophisticated methods for facilitating the body’s natural healing process. Those include peat baths, warm 20-minute soaks with pain-relieving minerals. They also include alternating hot and cold treatments to facilitate muscle recovery. One popular regimen is showers of three minutes hot water followed by 30 seconds cold water, repeated several times. Constitutional hydrotherapy, a distinct method, stimulates the body’s vital force and immune system through hot and cold towels and electrotherapy devices.

Students train in these techniques under faculty supervision at the University’s teaching clinics in Seattle and San Diego. Through the Nature Cure Club, they also use the classic medical-school model of “receive, give and teach” for learning procedures, Gordon says.

Teaching Patients

Naturopathic medicine students begin learning hydrotherapy in their first-year Physical Medicine 1 class, trying several therapies at home and writing about the experience. Nate Petersburg, a third-year student, had a head cold when he tried the “wet sock treatment”: going to bed in cold wet socks (with dry socks on top of them). He awoke with dry feet — and a clear head.

Naturopathic medicine students begin learning hydrotherapy in their first-year Physical Medicine 1 class, trying several therapies at home and writing about the experience. Nate Petersburg, a third-year student, had a head cold when he tried the “wet sock treatment”: going to bed in cold wet socks (with dry socks on top of them). He awoke with dry feet — and a clear head.

“It really works,” he says. “It draws the blood out of your head and eases congestion so you can sleep well.”

That helped kindle an interest he hopes to use in his future practice. “I want to teach patients things they can do at home,” he says. “Then it’s affordable for them.”

Gordon has already found hydrotherapy useful. As a registered nurse, she works weekends at the University of Washington Medical Center, using simple methods like ice for sprained ankles. She recalls one patient experiencing severe headaches. Gordon offered an ice-cold washcloth for one minute, alternated with a warm washcloth for three minutes.

“It helped,” says Gordon. “She felt better, and we didn’t have to worry about pharmaceutical interactions. And it empowered her to do it later at home.”

Deep Roots, Modern Uses

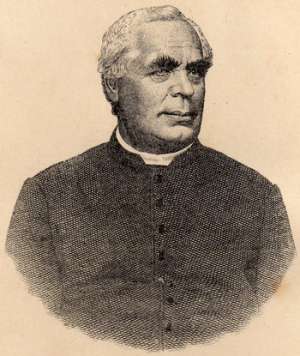

Modern hydrotherapy harkens back to the German roots of modern naturopathic medicine. Sebastian Kneipp, a Bavarian priest born in 1821, popularized a system of using alternative temperatures and pressures of water to encourage healing. His “Kneipp Cure” method spread through naturopathic leaders like Benedict Lust and was eventually adopted by Seattle’s Dr. John Bastyr, the University’s namesake.

Modern hydrotherapy harkens back to the German roots of modern naturopathic medicine. Sebastian Kneipp, a Bavarian priest born in 1821, popularized a system of using alternative temperatures and pressures of water to encourage healing. His “Kneipp Cure” method spread through naturopathic leaders like Benedict Lust and was eventually adopted by Seattle’s Dr. John Bastyr, the University’s namesake.

Each September, a faculty-led group of students spends two weeks in Germany studying the history of hydrotherapy. The Spa Medicine in Germany trip helps them learn about Kneipp hydrotherapy techniques, lymphatic drainage, connective tissue massage, sports therapy and aqua wellness. They also talk to practitioners about the German system of medicine, rehabilitation and spa management.

At Bastyr, students learn specific techniques and, importantly, how to customize them for the needs of each patient. Much of hydrotherapy rests on water’s ability to conduct heat, Dr. Neary says. Heat increases blood flow, relaxes muscles and increases tissue metabolism, while cold does the opposites, tonifying muscles and reducing inflammation.

For all the advances in medical technology, hydrotherapy has remained an essential part of medicine, he says. Just look at the training rooms of professional sports teams.

“If you go to the Seahawks or Mariners training rooms, there’s a lot of wealth and technology in those organizations,” Dr. Neary says. “But they’re using hot tubs, ice tubs, hot packs, cold packs, whirlpool baths and such. That’s all hydrotherapy.”